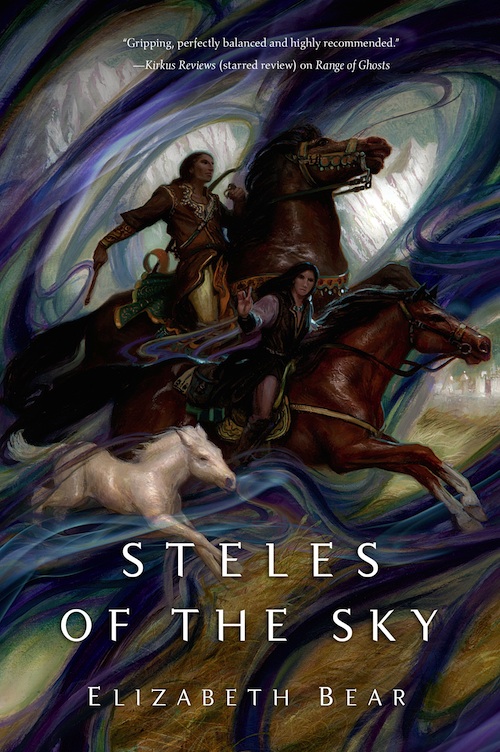

Check out Elizabeth Bear’s Steles of the Sky, the conclusion to her her award-winning epic fantasy Eternal Sky trilogy, available April 8th from Tor Books.

Re Temur, legitimate heir to his grandfather’s Khaganate, has finally raised his banner and declared himself at war with his usurping uncle. With his companions—the Wizard Samarkar, the Cho-tse Hrahima, and the silent monk Brother Hsiung—he must make his way to Dragon Lake to gather in his army of followers.

But Temur’s enemies are not idle; the leader of the Nameless Assassins, who has shattered the peace of the Steppe, has struck at Temur’s uncle already. To the south, in the Rasan empire, plague rages. To the east, the great city of Asmaracanda has burned, and the Uthman Caliph is deposed. All the world seems to be on fire, and who knows if even the beloved son of the Eternal Sky can save it?

1

Temur sat cross-legged on warm stone. Brother Hsiung had brought him tea. Contents untasted, the cup cooled in his hands. The sound of a mountain stream rattling over rocks rose from the bottom of a gully several li below and to his left, but he had lost his immediate awareness of it.

He was watching his mare chase her colt around the twilit meadow while the chill of evening settled on his shoulders. Bansh was of the steppe breed, and her liver-bay coat gathered the dim light and gleamed like shadowed metal… but the colt, Afrit, was the unlucky color called ghost-sorrel, and he shone through the gloaming like a pale cream moon.

Beyond them, the shaman-rememberer’s mouse-colored mare watched, dark eyes in a face white from ears to lip giving her an uncanny resemblance to a horse whose head was a skull. She stood quietly, a mature and stolid creature with her ears pricked tip to tip, seeming amused by the romping of more excitable beasts.

Beyond her, strange jungles that had long overgrown the city called Reason were awakening for the night. Feathery ferns unscrolled from their stony daytime casements. Toothed birds whose legs were feathered jewel-blue and violet like a second set of wings crept from crevices and shook the plumage on their long bony whip-tails into bright fans.

Afrit bucked and snorted, shaking the bristle of his mane. His legs—seeming already near as long as his mother’s—flashed even paler than his cream-colored body, as if he wore white silk stockings gartered above each knee. Bansh stalked him, stiff-legged, head swaying like a snake’s. The colt hopped back nimbly for one less than a day old, whirled, bolted—and tumbled to the ground in a tangle of twig-limbs.

He scrambled up again and stood, rocky on splayed legs, until Bansh ambled over and nosed him carefully from one end to the other. By the time she reached his tail, he’d remembered about the teat, and was busily nursing.

Temur sipped his cold tea. Afrit would have his mother’s higharched nose and good deep nostrils, the fine curve of her neck—even more dramatic with a stallion’s muscle on it. He’d have her neat, hard feet. The open questions were whether he’d ever be able to run on air the way his ever-so-slightly supernatural mother did… and what his unlucky, impossible color might presage.

Temur did not look up at the footstep behind him. He knew it: the hard boots and swish of trousers of the Wizard Samarkar. He played a game with himself, imagining her face without looking at her, and breathed deeply to catch the scent of her hair as she settled beside him. He was disappointed: it smelled of dust, and the desert, more than Samarkar.

But her shoulder was warm against his. She leaned into him, reached over. Plucked the cold bowl of tea from his hands and replaced it with one that breathed lazy coils of steam. He lowered his face to the warmth and inhaled. Moisture coated his dry nose and throat.

In pleasure, he sighed.

She drank down the cold tea and set the bowl aside as he turned to her. As always, her real face was far more complex than the one he held in his memory. He never quite remembered the small scar through an eyebrow or the slight irregularity of her nose.

It made him wonder how well he remembered Edene, who he had not seen since the spring.

The stars were shimmering into existence in the deepening sky, constellations he’d known all his life and yet had recently wondered if he’d ever see again. The Stallion, the Mare. The Oxen and the Yoke that bound them. The Ghost Dog. The Eagle.

It was strange seeing them framed in mountains on all sides.

“Are you hungry?” Samarkar asked at last. “Hsiung is making something. Hrahima is… off. Somewhere. And the shaman-rememberer is sleeping.”

“I’m waiting for the moons,” Temur said. She’d know why; one moon would rise for every son or grandson of the Great Khagan still living.

Temur was checking on his family.

A faint glow limned the ragged outline of the mountains to the east. When Temur glanced west, the stark light made the forested lower slopes there look like the rough undulations of the scholar-stones they carved in Song. Glaciers and smears of early snow glistened at their peaks, broken by the black knife-lines of ridges. His heart squeezed hard and fast, as if a woman caught his eye and smiled.

He looked away as long as he could, though Samarkar reached down and threaded her fingers between his. When he drank the last tea from the bowl he still held in his right hand, it was barely warm.

He set it on the rock beside him and turned to the rising moons.

Once there had been hundreds, a gorgeous procession scattered across the night, light enough to read by. Now a scant double handful drifted one by one into sight. There the Violet Moon, smeared with color like chalk, of Nilufer’s son Chatagai. There Temur’s own Iron Moon, red and charcoal and yet streaked bright. He waited for the pale circle of Qori Buqa’s Ghost Moon, just the color of Afrit’s creamy hide—

It did not rise.

Only Samarkar’s breathing told him she was in pain. He had clenched his hand through hers, and must be squeezing the blood from her fingers. When he forced his to open, his own knuckles ached. He stroked her palm in apology; briefly she encircled his wrist.

“Who?” she asked.

He shook his head, but said, “Qori Buqa is dead. If the sky can be trusted—”

“What can be trusted, if the sky cannot?”

He tipped his head in acquiescence. “Who killed him?”

“Another rival?” But she did not sound confident. “Some Song general? Does it change anything? We’ll still have to fight someone.”

He was silent a long time before he answered, “It’s the way the mill of the world grinds.”

She too left the quiet fallow between them for a while before she asked, “Have you dreamed this?”

His dreams—shamanistic, not quite prophetic—dated from before the blood-vow that was the reason she had originally chosen to follow him. It had been her wizard’s scientific bent that had brought her along, in order to study the progress of his oath—that, and a loyalty to her sister-in-law Payma, whom they had smuggled out of the Black Palace one step ahead of the guards.

He shrugged. “Not exactly. I dreamed Qori Buqa backward upon a red mare. That could be death. Or it could mean that he goes blind to war.”

“Went blind,” Samarkar corrected. “He’s not going anywhere now.”

“Except on vulture wings,” Temur replied.

When Temur looked up again, a moon he’d never before seen, a moon banded with rippled dark and bright like the temper-water of a blade, rode among its cousins in the old familiar sky.

Namri Songtsan I—by the forbearance of the Six Thousand Emperor of Rasa and Protector of Tsarepheth, Lord of the Steles of the Sky and a dozen other titles, though no one had called him by them yet—opened his toothless red-gummed mouth and squalled. The equally unheralded Dowager Empress Regent of the Rasan Empire, Yangchen-tsa, turned her face away from the work of dusty stonemasons. She pulled her wide silken wrap collar aside and put her son to her breast. But as was his not-infrequent habit, he gnawed the chapped nipple and would not latch. He turned his head aside, then craned the oversized thing back and began to scream like a peacock set live in a fire.

Which of my husband’s ancestors come back are you, little monster? Yangchen thought with the blend of affection and exasperation that seemed to her to be all parenthood was made of. A tyrant, that’s for sure.

She drew a breath—a mistake; it was full of smoke and the first tang of rotting flesh. She wanted to hug Namri to her heart. She wanted to drop him over the side of the building and clap her hands to her ears and scream right back at him.

Instead, she jerked her collar closed and thrust the screaming boy at his closest nurse, then turned back to the thing she had wished she could ignore.

She stood on a hastily constructed platform on the roof of the house of a lesser—but wealthy—noble family, surrounded by such of her husband’s royal court and inner circle as had survived. They overlooked the place where the Black Palace of Tsarepheth had stood. The aroma of burnt black powder still hung on the air. The riots of the previous day had sputtered into quiescence, and Yangchen had heeded the advice of the wizards and set up soup lines and first-aid stations where anyone could be fed or seen to, no questions asked. That might prevent a resurgence.

Another skinless corpse had been found nailed to a temple door, however. And her agents reported muttering that the smoke billowing from the Cold Fire sometimes took the shape of a malevolent face, pale sky staring through the empty whorls of its eyes.

The wizards said at least one of their agents reported more and more rumors of the Carrion King stalking the cold streets by night. Perhaps Yangchen had that rumor as much as the chill of encroaching winter to thank for the dissolution of the riots, come nightfall.

As for the palace—it had not been destroyed completely. One tower and a portion of the north wall had crumbled, the precisely hewn basalt stones blasted from their place by the force of the explosion. Yangchen could see clearly into several of the chambers and corridors, and she had an exquisite view of the workers below. Both stonemasons and rough laborers toiled—the laborers hauling cracked and collapsed stone, the stonemasons determining which rubble could safely be moved without collapsing the whole pile. The destroyed portion had contained the emperor’s apartments and the council chamber.

The limited destruction was why two of her son’s nurses were beside her, and her sister-wife Tsechen-tsa, and stooped old Baryan, with his spotted head uncovered because all of his hats were inside the ruined palace. That was why she was flanked by her husband’s advisors—her own advisors now—Gyaltsen-tsa and Munye-tsa, and not the whole of the council. It was also why the sun overhead was wrong and strange, a flat-looking pale yellow thing that seemed too hot and too close.

Yangchen-tsa closed her hands on the splintery wood of the unlacquered railing. She did not quite trust it to lean against. She’d scrambled up the ladder to watch this process because she felt it was her duty. Because she could not be entirely certain that this, too, was not her fault.

So many things were turning out to be.

There was no one Yangchen could speak to for comfort. Her only peer in the world was Tsechen, who stood beside her tall and impassive, with her hair undressed and her hands folded inside the sleeves of the soot-stained robe no one had been able to convince her to exchange. Yangchen’s clothes were fresh because she had been out of the palace when the detonation came, disguised as a commoner to confer with the wizards in their Citadel without her husband’s knowledge, and Baryan would not hear of her being seen as the empress regent in those wool and cotton rags.

Across the entire breadth of the city, even the ancient white walls of the Citadel had rattled with the force of the explosion, and she had stood beside Hong-la and his colleagues and watched smoke rise from the place that had been, for six years, her summer home.

Yangchen had had a mad urge, then, to take her son and head north, to keep her peasant garb and raise Namri as a—a calligrapher, an apothecary, a goatherd. Anything but an emperor.

Even as it occurred to her, she knew it for the fantasy of a child deluded by storybooks. Kings did not disguise themselves as noodleshop proprietors. Empresses—even empresses widowed at the age of nineteen—did not toss everything aside and go running off to make a living by their fancy needlework.

Still, Yangchen was tempted. And she might have done it—except for the abiding horror that this, like so much else, was something she had caused to be done.

She could face the guilt for her own actions, her own ruthlessness. Her father had warned her it would be necessary, when she married both the future Emperor of Rasa and his brother. She could face the deaths—and the subtler wickednesses—that lay against her own choice, her own hand. It was harder to accept the evils she suspected she had been manipulated into facilitating.

It was up to her to do something about that.

She squared her shoulders in the borrowed robe—too long— and turned to Gyaltsen-tsa. He was younger than many of her late husband’s advisors, closer to the age of the fugitive once-princess Samarkar. He had kind eyes inside a framework of character wrinkles and had affected fresh flowers woven into his braid. Yesterday’s still draggled there, sour and browning, petals transparent with bruises and folds.

“We cannot stay here.” Yangchen gestured to the work below. “This is fruitless.”

“Dowager,” Baryan said from her other side, thus becoming the first to speak her new title. “Your Imperial husband—”

She looked at him, hating how the tightness of her lower lip drew up at the center as she fought tears. Her glare silenced Baryan—or perhaps the silent glare of the strange sky above was answer enough to his protest.

“If my husband were alive,” she said, “would the sky have changed? Another God has claimed this land, na-Baryan. Shall we wait for his army to come?”

He looked down. “Your son—”

“Must be protected. He is the Emperor of Rasa now. And he should be in Rasa, under a Rasan sky, where we can make him safe.” She turned, away from the shattered tower, toward the southern horizon. They were high enough atop this commandeered house for an unobstructed view down the fertile valley. Yangchen’s gesture took in the cradling hands of the mountains, the hills that centuries of cultivation had carved into scalloped terraces, the many-bridged canyon of the river as it plunged from stone to stone, dancing between the walls it had carved for itself. In spring the fields would be a thousand shades from pink to green to gold; now they were russet and umber or silvery-green, fallow under winter cover. At least we got the harvest in.

But it wasn’t the fields she wanted her advisors to consider. It was the road that followed the course of the river, and the train of riders, walkers, and wagons—some one-wheeled, like giant barrows; some two-wheeled dog-carts; some four-wheeled for heavy hauling—upon it.

“With or without us,” Yangchen said, surprised at her own eloquence, “our people are leaving. The question before us is do we let them face the road alone—or do we go with them to Rasa, perhaps bring some wizards to protect them from the demonlings, and take the chance that we can save our empire?”

Baryan struggled for an answer. Yangchen knew he could out-argue her. She couldn’t afford to give him the opportunity. She turned to Gyaltsen, about to raise her appeal to his more sympathetic face—

A cry from below interrupted. Not my husband’s body, she prayed, turning back to the rail—even as she prayed that it was. She knew Songtsan was dead, knew it in her bones, knew it by the sky. But was it better, somehow, to hold a tiny fragment of uncertainty, of half-hope— or was it better to know unequivocally?

There was a flurry of activity among the ruins. Someone—one of the master stonemasons—was rushing to the ladder, climbing the wall of the appropriated house with one hand because a cloth sack swung in the other. He had his hands upon the rail where Yangchen’s hands had a moment before rested. Stone dust smeared his clothing and lightened his face. Strange, Yangchen thought with a terrible disconnection. You’d think the dust of the Black Palace would be dark—

“Dowager,” the stonemason said, dropping his eyes abruptly. “Secondwife—”

Tsechen stepped forward. The hem of her dirty robes trembled against her shoes. Her hands knotted before her breast. She opened her mouth and made no words—just a moan.

“Honored sister-wife,” Yangchen said, placing one hand in the crook of Tsechen’s elbow. “Permit me.”

The look Tsechen gave her was not comfort but rage, but the anger seemed to strengthen her. She closed her mouth and did not draw away. “Honored master mason,” Yangchen said. “What have you found?” He stared at her for a moment longer and then knelt at the edge of the roof, one knee braced against the platform edge. Yangchen wondered how he did not tumble to his death, but masons must be used to scaffoldings. He reached into the mouth of the bag, fumbled, and with

unsteady hands jerked it wide.

What he drew forth was the carven crown of Rasa, a spiked filigree

circlet of oil-green olivine and peridot embedded in a matrix of opaque, crystalline gray iron, just as it had been cut from a piece of skystone on the command of Genmi-chen in the same year the Citadel was founded. Head lowered, he reached through the gaps in the railing and extended it up to Yangchen-tsa.

She took it in her hands. She had never been suffered to touch it before, and was surprised at its coolness and weight. It was smooth, as her fingers played over it, with only the faintest catch of changing texture where the stone and metal met. She turned it in her hands, the incredible delicacy of the filigree suggesting the forms of dragons, phoenixes, the Qooros. More familiar beasts—carp, hounds, serpents, tigers— were layered within, visible beneath the outer layer of pierced and lacecarved stone.

“It’s so heavy,” she said.

“Madam,” said the stonemason. “We have uncovered the treasury.”

Munye-tsa gasped. “Six Thousand heard you,” he said, laying a subtly restraining hand on na-Baryan. “It is a sign.”

Lightning throttled the column of ash and smoke writhing up the sky behind the refugee caravan. The Wizard Tsering—awkward astride a mare so weary the beast struggled to raise her head—had paused at the peak of a pass, reined her mount aside, and turned to look back along the snaking column. Groups of Qersnyk nomads and clumps of townsfolk from Tsarepheth trudged up the rise, heads as low as the mare’s. The train had spread out across the bottom of the valley; where the path ascended they fell naturally into single file again, winding up a series of switchbacks so steep Tsering-la could have dropped a persimmon on the head of someone below… had she a persimmon to spare.

Feathery ash blossoms starred her mare’s shoulders like snowflakes. The horse could have passed for one of the Qersnyk fancies with their spotted coats, but these spots smeared and gritted in the mare’s sweat when Tsering-la passed her hand across them. She had abandoned trying to brush the ash from the mare, from herself, or from her hat brim, but she still patted the horse’s shoulder. She was unclear as to which of them she was trying to reassure.

A vaster billow of smoke rolled out, down the distant flanks of the Cold Fire, to disappear behind the shoulders of nearer mountains. Tsering could imagine she caught the red glow behind it, but it was likely only the lightning. The earth dropped underfoot—suddenly, sickeningly, like missing a stair. Tsering clutched the pommel as the mare snorted and kicked out, too exhausted for more than a halfhearted attempt at panic. Behind and below, most of Tsering’s fellow refugees did not even raise their heads.

You could even become used to a volcano—or too tired to care about it anymore. Although the eruption seemed to be worsening as wizards fled the Citadel, their strengths no longer combined to restrain it.

She wondered if this billow of ash, this shaking of the earth, was the one that heralded the failure of those wizards still left behind at the White-and-Scarlet Citadel of Tsarepheth to protect it, the city that shared its name, and the plague victims too weak to be moved— and who would have no hope of surviving away from the brewing vats of Ashra’s healing ale. The master of Tsering’s order, Yongten-la, and the others who remained behind were risking their lives for the sick— and for the Citadel, with its libraries and laboratories harboring irreplaceable centuries of knowledge.

There was very little those who were not wizards could do to protect themselves if the Cold Fire decided to kill them. And as for the wizards… Tsering had never found her power. All her theory, all her understanding of the mechanics of how the universe worked, would not avail her if a blast of superheated poisonous gases pushed a wall of ash and stone down on them, if molten glass rained from the sky.

She wondered if even Hong-la could manage to protect anyone, protect himself, in such a case as that.

As if her thoughts had been a summoning—and surely even the master wizard from Song could not hear minds—the tallest walker toiling up the path below raised his head and looked up at her. Even at a distance, the gesture revealed the strong lines of a long-jawed, rectangular face beneath the sloped brim of his hat. It was a peasant’s cap, meant to shade the head and shoulders while working under the blazing sun, and it did a remarkable job of shedding ash. Trust Hong-la to recognize the easiest, most elegant solution.

Wait there, he mouthed.

Tsering raised a hand in acknowledgment. Her throat burned with the fumes of sulfur. She soothed her mare again and watched Hong-la climb. Eventually, it occurred to her that she could dismount and offer the horse water. She was no expert rider, preferring shank’s mare—or soul’s—to the actual sons of the wind, but she ran her hands down the mare’s legs and checked her feet, wondering how she would know if something was wrong and—if she found it—what she could do about it.

Samarkar, with her noble past, would have known how to care for the horse. Or Ashra, who had spent so many years among the Qersnyk. But Samarkar was far away, if she were even alive still, and Ashra…

Ashra was not alive.

Reminded, Tsering touched the saddlebags for reassurance, feeling the resilience of cloth and the weight of stones within. Those objects were the reason why she rode rather than walking. Tsering-la was one of the wizards and shaman-rememberers entrusted with carrying the wards, a cowing responsibility.

As she was placing the mare’s last hoof gently on the ground once more, the steady rhythm of trudging feet, clopping hooves, and turning wheels cresting the pass and starting down the other side was broken as carters and walkers hesitated in order to stare. She turned, and found Hong-la beside her—arms folded, chin tucked, standing on air as if it were a solid stone platform. He had levitated himself from his place below more easily than she could have scrambled up the slope.

She bit down on her reflexive envy and turned to him as he stepped forward sedately, his split Song-style boot coming to rest on the stone of her vantage point.

Tsering thought of Hong-la as a sort of human Citadel, a broadbuilt, bony tower of intellect and impervious strength. It was a shock to see his complexion faded and grayish, the smile and concentration lines beside his eyes furrowed so deep they seemed inflamed. His usually cropped hair, twisted into sweaty spikes by the exertion of the climb, protruded raggedly around the perimeter where his hat rested against his scalp. It seemed grayer, even—but that might be the ash.

“You’re another Tse-ten of the Five Eyes,” she said, shaking her head in awe.

“The Process of Air wants to lift us,” he replied. “Encourage that, discourage the Process of Earth that wishes to hold us close, and one can drift like a feather on the wind.”

“If it were as easy as that, it’d be the first trick any wizard learned,” she said. “I don’t think Master Yongten could manage that.”

He harrumphed, and Tsering held out the waterskin. “We could be doing this at the height of summer,” she said, by way of apology— though why she felt the need to apologize for eruptions and revolutions was beyond her.

Hong-la took the skin in his long, heavy-boned hand. Like most wizards, his fingers were decorated with a fascinating assortment of scars. He drank water sparingly and sighed. “We wouldn’t be racing winter, then.”

“Finish it,” Tsering said. “There should be water in the next valley.”

“If it’s not full of ash.” He handed her back the skin.

“I’m full of ash. Why should what I’m drinking be any different?” She hung the skin back on the saddle, where it hung forlornly slack. They’d need to filter water that night if they did not find some fresh. One more task to exhaust the too-few wizards among them. Hong-la should by rights be sleeping along one side of a single-wheeled cart by day, but who could rest rattling over these trails? In a cart that could tip down a cliff with one misstep?

She and Hong-la rejoined the column, Tsering leading the mare. The refugee train moved at a dragging pace determined by the Qersnyk carts and oxen. Tsering did not have the energy to chafe at it. Instead, she watched the road before her feet—because looking at the horizon was too exhausting—and lifted her gaze only occasionally to see how far she had come. Beside her, Hong-la toiled uncomplainingly—but he leaned on a twisted stick, something she had never seen him do before. The gnarled wood was smooth-polished, carved to accentuate its natural curves, and glossy beneath the dust and ash. Tsering thought it was Song workmanship, and wondered if he had brought it with him all that way, when he had come to the Citadel to become a Wizard of Tsarepheth.

Another day, she might have asked him. Now it was all she could do to raise a foot and put it before the other.

Just keep walking. It was a philosophy that had gotten her through worse losses—or at least more personal ones—than this.

Steles of the Sky © Elizabeth Bear, 2014